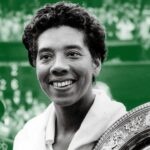

June 26, 1951: The day Althea Gibson became the first black player to compete at Wimbledon

Every day, Tennis Majors looks back at the biggest moments in tennis history. On June 26, 1951, the legendary Althea Gibson became the first black player to compete at Wimbledon

Althea Gibson became the first black tennis player to claim a Grand Slam title on this day May 26, 1956.

Althea Gibson became the first black tennis player to claim a Grand Slam title on this day May 26, 1956.

What happened exactly on that day and why it is memorable in tennis history

On this day, June 26, 1951, Althea Gibson became the first black player to ever compete at Wimbledon. It was the outcome of a long process against racism and prejudice, which Gibson had to face before she was allowed to compete in major tennis events.

She only reached the third round that year, but six years later, in 1957, after having won Roland-Garros in 1956, she became the first black player to lift the trophy at the All England Club. Her success was a big step in favour of the desegregation in tennis as well as the movement for civil rights.

The place: Wimbledon

Wimbledon is the oldest and the most prestigious tennis tournament in the world. Held at the All England Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club since 1877, it moved to its current location in 1922, the same year when the Centre Court was built.

Considered by many as the most intimidating court in the world, with its famous Rudyard Kipling quote above the entrance (“If you can meet with triumph and disaster and treat those two impostors just the same”), the Centre Court had seen the best players of all time competing for the title.

Wimbledon was played on grass, a surface that is usually more suitable for serve and volley players. It also maintained old-fashioned traditions such as the white dress code and the fact that the defending champion was always the first to play on the Centre Court.

The facts: Althea Gibson’s long journey to compete at Wimbledon

Althea Gibson was born in 1927 on a cotton farm in North Carolina, but she grew up in New York, where her family, hit by the Great Depression, moved in 1930. She made her debut with a racket in the streets of Harlem, playing paddle-tennis, a game adapted from tennis, played on a smaller court without double lanes (not to be confused with the sport known as padel in modern days).

Young Althea quickly became good at this game and was the New York paddle champion in 1939, at the age of 12. Thanks to a collection made by her neighbours, she had the opportunity to become a member and take lessons at the Harlem Cosmopolitan Tennis Club, a club for African American players.

In 1941, Althea Gibson started to play in the American Tennis Association (ATA), the African American equivalent to the USLTA. With famous boxer Sugar Ray Robinson’s financial help, Gibson captured junior national championships and in 1947 won the first of 10 straight ATA national women’s titles. Her strength and speed allowed her to dominate the court.

Her successes were noticed by benefactors Walter Johnson and Hubert A. Eaton. With their help, she managed to enter bigger tennis events, but the USLTA tournaments remained closed to her. The USLTA officially didn’t authorise racial segregation in tennis events, but many of its tournaments were actually held in all-white country clubs. Eventually, Althea Gibson set foot in this world in 1949, becoming the first black woman to compete at the USTA’s National Indoor Championships, where she reached the quarter finals.

But it was not before 1950 that she could participate in the most important tournament held by the USTA, the National Championships in Forest Hills. After she had been denied access to the draw several years in a row, it took the intense lobbying of former champion Alice Marble to force the organisation to let Gibson compete.

In a letter to the USLTA Magazine, Marble wrote: “If tennis is a game for ladies and gentlemen, it’s also time we acted a little more like gentle-people and less like sanctimonious hypocrites…. If Althea Gibson represents a challenge to the present crop of women players, it’s only fair that they should meet that challenge on the courts.”

Gibson was then admitted at the Forest Hills tournament and won her first round against Barbara Knapp, before losing to Louise Brough, defending Wimbledon champion, in a match played over two days because of a rain delay.

It was a moment of tennis history, as sports writer David Eisenberg told Sports Illustrated, “I have sat in on many dramatic moments in sports, but few were more thrilling than Miss Gibson’s performance against Miss Brough. Not because great tennis was played, because it wasn’t. But because of the great try by this lonely, and nervous, coloured girl.”

Gibson’s inclusion in America’s biggest tennis event was not just the story of a tennis player making her way to the top. For the African American community, this was comparable to what Jackie Robinson had done in baseball before: a milestone in the fight for civil rights.

In July 1951, she became the first black woman to play at Wimbledon. Her entourage had tried to convince the All England Club board to invite her into the draw two years before, but at the time, the British officials had suggested that she first competed in tournaments held in Bermuda. Gibson did so, and after having claimed her first international title at the Carribean Championships in Jamaica, she flew to Bermuda, where she also won the tournament. With such persistence, she didn’t leave a choice to the officials, who finally invited her into the draw.

Althea Gibson’s debut was successful: despite the pressure of being the first black player to ever compete at Wimbledon, she prevailed against Pat Ward, from Great Britain (6-0, 2-6, 6-4). According to the Associated Press, although she was unseeded, Gibson “convinced the British experts that she had the equipment to rank high in the world within another year or two.”

What next: Althea Gibson will shake hands with Queen Elizabeth II

Althea Gibson would be defeated in the following round by the fifth seed, Beverly Baker (6-1, 6-3). She would be so disappointed by this loss that she would even consider quitting tennis to join the army. In 1956, at Roland-Garros, Althea Gibson became the first black athlete to triumph in a Grand Slam tournament. The following year, in 1957, Althea Gibson would achieve new milestones, triumphing at Wimbledon and the US Open.

At the All England Club, she won in front of Queen Elizabeth II: “Shaking hands with the queen of England,” she said, “was a long way from being forced to sit in the coloured section of the bus.” On July 11, coming back to New York, she became only the second Black American, after the 1936 Olympic champion Jesse Owens, to be honoured with a ticker tape parade. In 1958, she would become the first black woman to make the cover of Time and Sports Illustrated.

In total, Gibson would claim five Grand Slam titles in singles, five in doubles, and one in mixed doubles.