Big forehand and physicality, but very different styles: differences and similarities of Ruud and Alcaraz’s games

Carlos Alcaraz and Casper Ruud, who will compete for their first Grand Slam title tonight – and the No 1 ranking – in the US Open final, both rely on the forehand and physical intensity. Yet they have many differences, some glaring, others nestled in the detail of the statistics

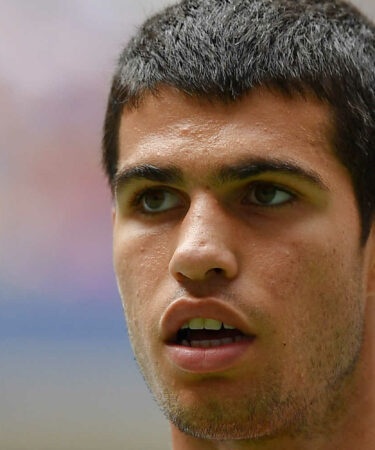

Carlos Alcaraz and Casper Ruud before the US Open final | © AI / Reuters / Panoramic

Carlos Alcaraz and Casper Ruud before the US Open final | © AI / Reuters / Panoramic

What will make the difference between Carlos Alcaraz and Casper Ruud in Sunday evening’s US Open final? The ranking and the insane level, in any case the one that we have seen through six rounds during this US Open, leans in favour of the Spaniard; Experience and physical freshness, on the other hand, tilts to the Norwegian side.

The management of inevitable nerves that come in a Grand Slam final? We don’t really know anything about it.

There remains the purely technical-tactical part, which is not the least important, even if we know that a Grand Slam final is often decided by more than simply tennis.

We have two players there who do not seem to arouse the same emotions with the public – it is day and night between the hair-raising electricity of the youngest and the modest coldness of the eldest – but they nevertheless both rely on similar methods.

Their strengths, we know them. Especially those of Ruud: a huge, disruptive forehand, with which he lands an average of 65 percent of his strikes, even if it means sometimes shifting his court positioning dangerously to the backhand side; and stamina not to be taken for granted, like this eye-opening exchange of 55 strokes at the end of the first set of his semi-final with Karen Khachanov.

Wow, how Ruud.

For Alcaraz, it’s a little more complex, probably also because it’s a little more complete, even if the prodigy from Murcia stands out above all for his firepower and supersonic explosiveness as a mover, as well as his endurance, which has had plenty of time to be tested during this gruelling US Open, and appears to be bullet proof.

Alcaraz also smothers his opponents with the intensity he puts into each exchange – will he be able to put as much on Sunday, after having played for over 13 hours in his last three matches, all of them five-setters? – and his strongest shot is unquestionably the same as Ruud: the forehand.

BACKHAND TO BACKHAND TO FOREHAND

The Norwegian possesses a rather asymmetrical game, therefore, devilishly effective on the forehand side and more vulnerable on the backhand side. So much for the main similarity between the tennis of Ruud and Alcaraz.

Ruud and Alcaraz, during their semi-final wins against Karen Khachanov and Frances Tiafoe respectively, took this similarity to the point of presenting exactly the same average ball speed in topspin forehand (79 mph, or 127 km/h) and backhand lift (72 mph, or 115 km/h).

(Statistics issued by the Hawk-Eye, to which Tennis Majors had access.)

Those same stats also tell us that Ruud and Alcaraz have a different way of using those two strokes from the baseline. The Norwegian, who is now the absolute benchmark on the circuit in this area, spins the ball a little more on the forehand (3243 rounds / minute, against 3005) and much more on the backhand (2618, against 1397). Causal link or not, surprise or not, Ruud also commits a few more unforced errors with the forehand, and Alcaraz a little more in the backhand.

For Ruud, it is a backhand that he likes to avoid; it is true (41 percent of backhands hit on average in the exchange in the semi-finals, against 36% for the Norwegian).

Then the question of the serve: in this sector of the game, the Norwegian has been more effective since the start of the tournament, with a better total of aces (36 against 27 for the Spaniard, who also had longer matches) and a significantly better percentage of points earned behind his first ball.

Visually, however, Alcaraz’s serve is more “flashy”, with a first offering that goes faster in peak speed and second that possesses a huge kick. But in the overall game, in stamina/speed and stamina/consistency, Ruud has been a better server here in New York.

He was also better, in the semi-finals at least, in another pattern that was even more fundamental for the two men: the serve-plus-one. Against Khachanov, when Ruud managed to play a forehand behind his first serve, Ruud hit the mark 82% of the time. It is enormous. Much more than the 72% – also very high – achieved by Alcaraz against Tiafoe.

Another main tactical key to this final could therefore be the way in which the two players will attempt to neutralize their opponent’s serve. Here, we come to one of the main differences of their games: the return of service.

More precisely, their positioning in return of serve.

TWO DIFFERENT PHILOSOPHIES ON RETURN OF SERVE

Again, this was particularly blatant in the semi-finals. With both pitted against a great server, Ruud and Alcaraz had two very different ways of going about their business. The Norwegian positioned himself much closer to return the opponent’s first serve, with a point of contact measured at an average of 1.45m behind the baseline, compared to 2.49m for the Spaniard.

On the other hand, against the second ball, it was the opposite. Curiously, Ruud chose to step back much more than in the first, with a point of contact measured in the semi-finals at 3.45m (!) behind the line.

While Alcaraz will more often look for the second opposing ball inside the court (29cm in front of his line on average against Tiafoe). His preference is therefore not to initiate the exchange but rather to inflict damage from the first stroke of the racquet. He is a puncher who seeks the knockout very quickly, while his rival likes to work the body.

This is also true against the first serve since we see that Ruud returns blocked 50 percent of the time, while Alcaraz is only 18 percent. Even there, the Spaniard refuses to submit. This results in more errors, perhaps. But also greater pressure put on the server. And, ultimately, a better percentage of points won behind the opposition’s first ball, throughout the tournament.

Unsurprisingly, Alcaraz also takes the ball earlier in the rally (37cm behind his baseline on average during his semi-final, against 71cm for Ruud), with the consequence of covering less ground. Thus, of the four semi-finalists, Ruud is the one who covered the most ground during his victory against Khachanov, much shorter than that of Alcaraz against Frances Tiafoe (the one who covered the least).

Alcaraz’s precision in this category could be useful in tempering the problem of the length of the matches the Spaniard has played, compared to those of the Norwegian.

Those are the raw statistics. But they will reset prior to Sunday. We must keep in mind that from one match-up to another, the equation can turn out to be very different.

Especially in a Grand Slam final, where the X factor often takes on disproportionate proportions.