From Gibson and Ashe to Osaka – tennis’s trailblazers for racial equality

The two-time Grand Slam champion Naomi Osaka followed in a brave and powerful tradition this week.

Althea Gibson became the first black athlete to win a major title on May 26th 1956

Althea Gibson became the first black athlete to win a major title on May 26th 1956

In a sport played, run and watched by people who are predominantly white, it can be difficult for black and indigenous people of colour to have their voices heard.

Two-time Grand Slam champion Naomi Osaka’s courageous and principled stance at the Western and Southern Open – stepping back from her scheduled semi-final match in solidarity with protests across the world, and in doing so pushing the entire event to go on hold for 24 hours – demonstrated just how much power leading players can have.

And it also demonstrated that black athletes feel able to speak publicly and protest the discrimination and racism they see.

“Racism is not only a ‘black issue'” (Venus Williams)

Venus and Serena Williams have been visible and vocal on issues of inequality for two decades.

“Speaking up about racism in the past was unpopular. It was shunned. No one believed you,” Venus wrote on Instagram earlier this year.

She urged her white counterparts and white people more broadly to speak up.

“Just as sexism is not only a ‘women’s issue’, racism is not only a ‘black issue’.

“When the majority groups stay quiet, when they sit in the chair of disbelief, they unwittingly condone the oppression of marginalised groups.”

Now Osaka is making a mark for the next generation.

“Before I am an athlete, I am a black woman,” Osaka wrote on social media. “And as a black woman I feel as though there are much more important matters at hand that need immediate attention rather than watching me play tennis.

“I don’t expect anything drastic to happen with me not playing but if I can get a conversation started in a majority white sport I consider that a step in the right direction.”

View this post on Instagram

But it has not always been that way.

Seventy years ago, the late Althea Gibson became the first black player to compete at the US Nationals, the forerunner to the US Open. She was playing at a time when many public places were still segregated – and that included tennis, with white and black players competing in separate events.

In 1949, Gibson played in the National Indoor Championships, the first black woman to take part in a USLTA-approved event – but nonetheless she was still not allowed to play in the US Nations.

A four-time Nationals champion – a white woman – stepped up to show her support, in an act that would surely be applauded by Venus Williams half a century later.

“She is not being judged by the yardstick of ability”

Alice Marble picked up her pen and wrote an eloquent editorial in July 1, 1950’s edition of American Lawn Tennis magazine.

She criticised the USLTA committee – and pointed out that if they were waiting for Gibson to win one of the major invitational tournaments before she could compete in the US Nationals, then that would never happen – because those tournaments would not invite her unless told to. It was a vicious circle of Gibson, and Marble was disgusted.

“She is not being judged by the yardstick of ability but by the fact that her pigmentation is somewhat different,” Marble wrote.

She blasted the sport’s personnel for acting like “sanctimonious hypocrites” than the gentlefolk they should be, and argued that Gibson deserved the opportunity to improve her game by playing against the best.

“She might be soundly beaten for a while – but she has a much better chance on the courts than in the inner sanctum of the committee, where a different kind of game is played.”

Gibson was subsequently invited to play in the US Nationals, and after she won her first-round match, Marble walked alongside her as she left the court – the first time the two had met.

Later, Marble wrote Gibson an open letter, in which she mentioned the opprobrium she had faced since her condemnation of tennis’s racism.

“People who had called me ‘Champ’ since 1938 suddenly remembered that I was ‘Miss Marble.’ People who had taken ostentatious advantage of our kissing acquaintance gave me a chilly handshake or failed to notice my approach, or glared, which was even funnier,” she wrote.

“They only remember a terrible article I wrote, saying that a good tennis player named Gibson ought to play in the Nationals.”

Gibson responded in kind, noting the number of black spectators who watched tennis for the first time when they saw her at the US Nationals, and thanking Marble for what she had said.

“I believe the new friends who believe in fair play and democracy will outnumber the few old ones you lost. At least they will have a more intrinsic value,” she wrote.

In 1956, Gibson became the first black player to win a Grand Slam singles title when she won the French Open, and followed it up the year after with a triumph at Wimbledon – and then the US Nationals.

She also teamed up to play doubles with Britain’s Angela Buxton, who had faced discrimination for her Jewish heritage – and the pair had a massive amount of success.

Power in unity and collective action

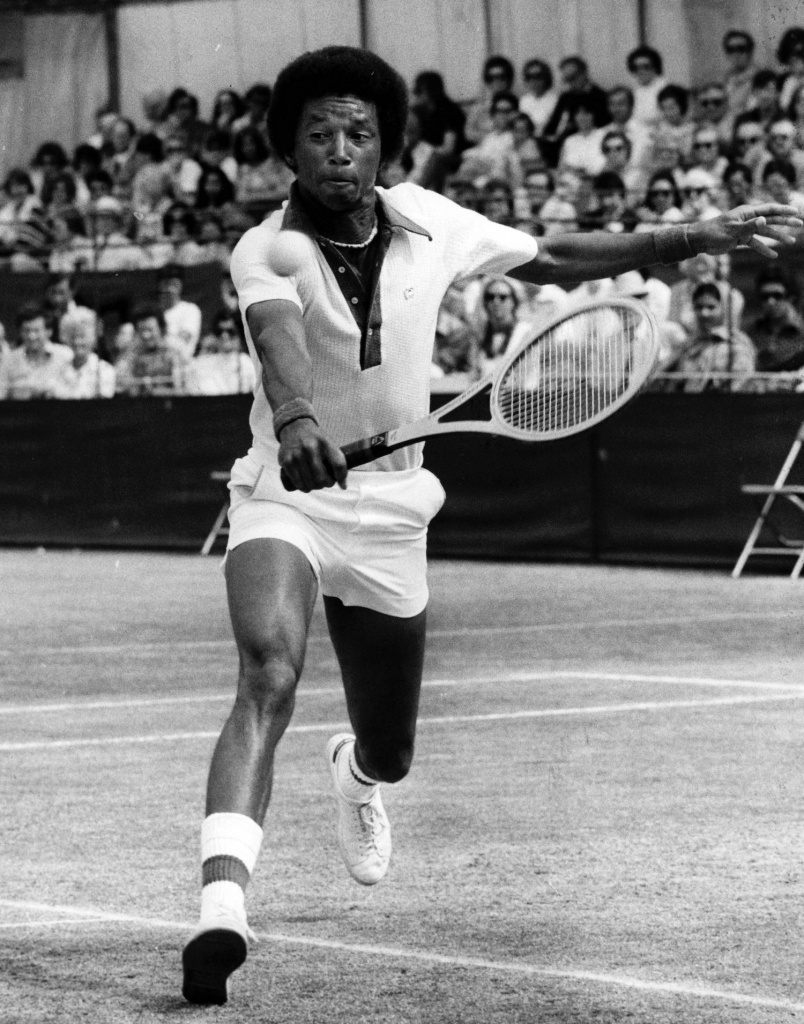

It was a decade later that Arthur Ashe followed in Gibson’s footsteps, winning the US Open in 1968, the Australian Open in 1970, and getting his first-ever win over long-time foe Jimmy Connors to win Wimbledon in 1975.

Ashe was always keen on using his public profile to make a stand, lobbying for a boycott of Wimbledon in 1973, ostensibly to support Nikki Pilic, who had been banned from the tournament for refusing to participate in one of Yugoslavia’s Davis Cup ties.

But it was also because professional players wanted to be able to enter whichever tournaments they wanted – rather than only participate in the ones their national federation signed them up for. If they happened to displease the federation for whatever reason, the chances were that they would not get to go to the biggest, most lucrative events. After the Wimbledon boycott, no federations tried to force players to take part in events again. It showed the power that players could have if they took action together and supported each other.

Ashe sometimes took stances that others fighting for the same causes may have disagreed with – for example, he played tennis in apartheid South Africa during the 1970s in the hope that he could prove the wrongness of their racist system through his tennis brilliance.

But he also acknowledged when he was wrong. In 1977, he announced that playing sport in South Africa had been the wrong way to effect change – and he had realised that when trying to buy tickets for a tennis match, and being directed to an “Africans only” counter because of the colour of his skin. After that, he joined the movement promoting a boycott. It was he who spoke to John McEnroe about his decision to play in South Africa in a $1m exhibition event – and apparently talked him round to change his mind.

A bronze statue of Althea Gibson now stands outside Arthur Ashe Stadium in the Flushing Meadows complex – a pair of heroes honoured for the part they played in creating the sport we have today.

And it was there on Wednesday night that Osaka stepped up in her own campaign for racial equality. Tennis may look more equal now thanks to the battles fought by generations before, but racism is still rampant in society – and now the former world No 1 follows in a brave tradition to become the sport’s latest trailblazer.

• Also read : Naomi Osaka, from a shy champion to a role model

• Also read : Western & Southern Open paused

• Also read : 14 players who have taken a stand on social issues