February 6, 1993: The day the great Arthur Ashe passed away, aged just 49

Every day Tennis Majors looks back at the biggest moments in tennis history. Today, we go back to 1993 to pay tribute to one of the few tennis champions whose impact went beyond his sport: Arthur Ashe, the first black man to ever win a Grand Slam tournament

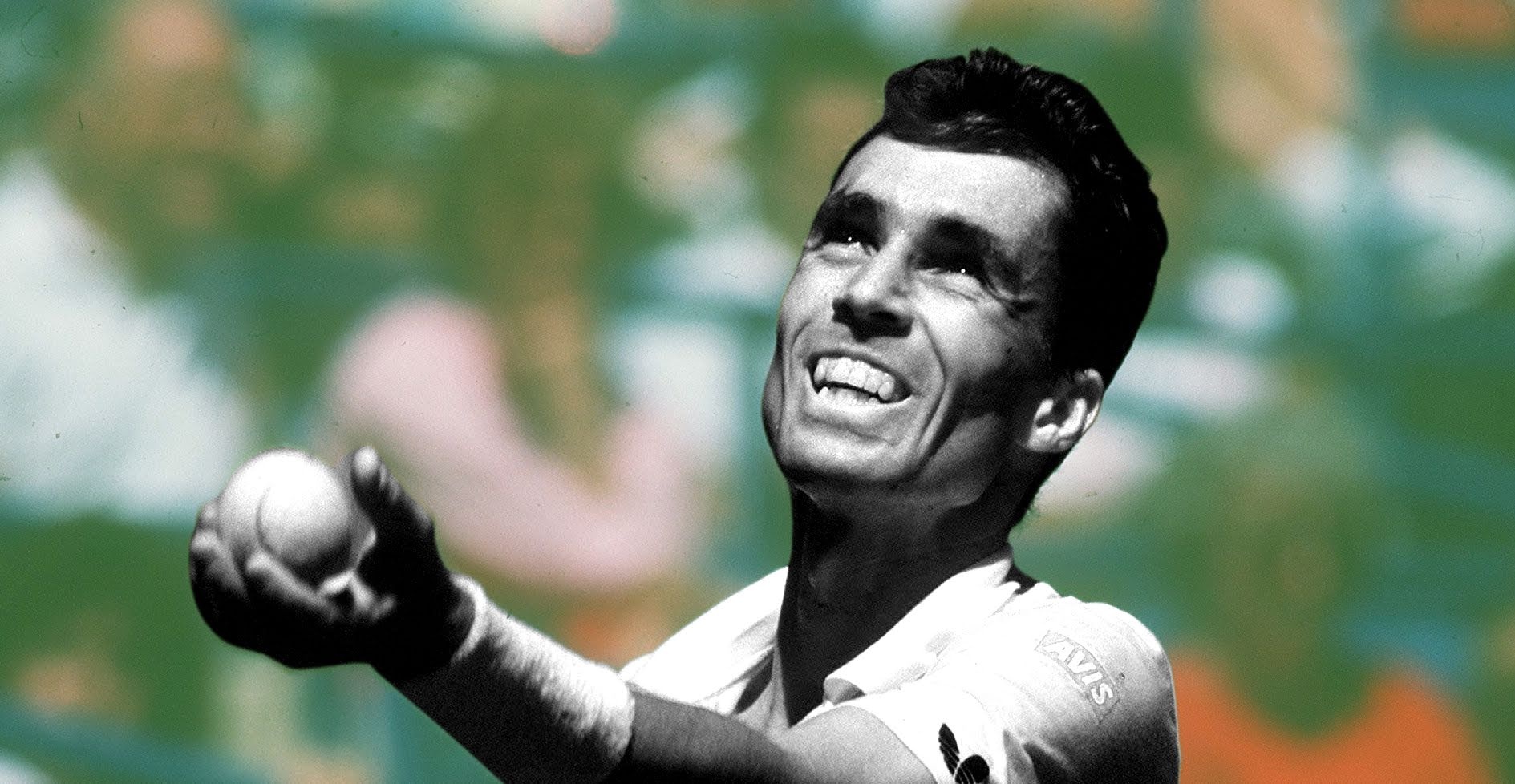

Prosport / panoramic

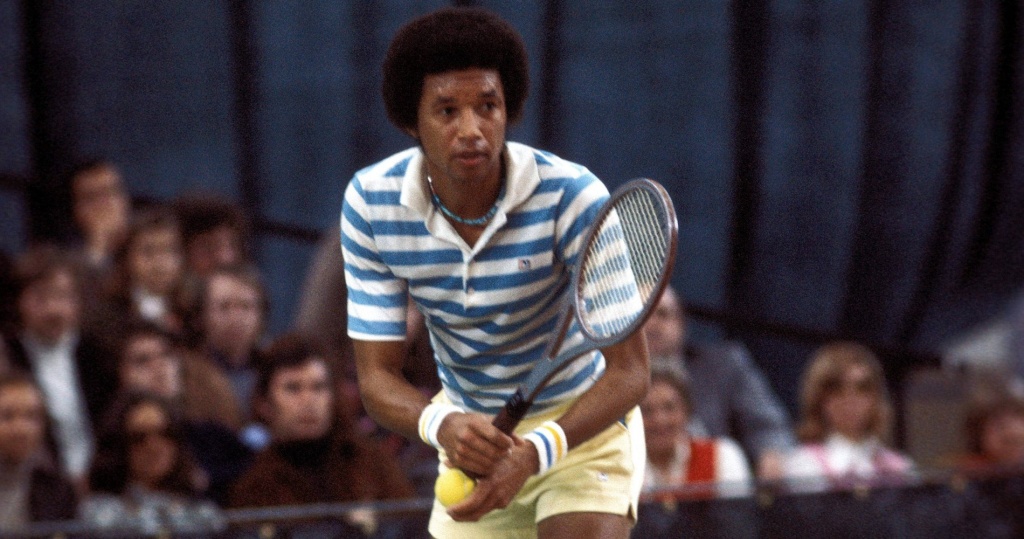

Prosport / panoramic

What happened exactly on that day

On this day, February 6, 1993, Arthur Ashe passed away at New York hospital from AIDS-related pneumonia. The three-time Grand Slam champion, former Davis Cup captain and civic rights activist had contracted the virus from blood transfusions he received in the early 1980s.

- Arthur Ashe, champion, legend, humanitarian

Arthur Ashe was born in 1943, in Richmond, Virginia. His father forbade him to play football, so young Arthur started to play tennis on public courts, where his talent was noticed by the best black player in Richmond, Ron Charity, who taught him the basics and later introduced him to Dr Robert Walter Johnson.

Dr Johnson was the coach of Althea Gibson, the first black woman to triumph in Grand Slam tournaments, and he took Ashe’s game to a next game, but he also prepared him to face racial segregation and compose with it. In 1963, Ashe became the first African American player to win the National Junior indoor title, and he was awarded a tennis scholarship to the University of California, Los Angeles. There, he could sharpen his game by practising with his idol, Pancho Gonzales, and the same year, he was the first black player to be selected in the United States Davis Cup team.

Before the 1968 US Open, Ashe had already claimed 31 titles, and he had finished runner-up twice to Roy Emerson at the Australian Open, in 1966 (lost in four sets, 6-4, 6-8, 6-2, 6-3) and in 1967 (defeated in straight sets, 6-4, 6-1, 6-1).

In September 1968, he took his career – and his life – to the next level when he defeated Tom Okker in the final of the US Open (14-12, 5-7, 6-3, 3-6, 6-3), to become the first African American male player to claim a Grand Slam title. It was not only a major achievement in his sports career, but it also gave him the opportunity to advocate for the civil rights movement.

Ashe, who still competed as an amateur in the first Forest Hills tournament in the Open Era, could not receive any prize money and left New York with $280 (fourteen days of $20 per day).

“That tournament was a transition in his life,” his brother, Johnnie, explained later. “No longer would he just be a tennis player as far as the public was concerned. Because those who didn’t know him didn’t realise how intellectual Arthur was, but they were about to find out.

“I think that him winning that and becoming the champion of the US Open opened up a whole new direction that he could take, because he knew he would be listened to. His opinions would matter.”

Arthur Ashe claimed two more Grand Slam titles, the 1970 Australian Open (defeating Dick Crealy in the final, 6-4, 9-7, 6-2), and the 1975 Wimbledon Championships (beating Jimmy Connors in the final, 6–1, 6–1, 5–7, 6–4). On top of that, the African-American champion finished runner-up in two other major tournaments (at the 1971 Australian Open and at Wimbledon in 1972).

Ashe’s last remarkable result happened at the 1977 Masters Cup, where he was defeated in the final by John McEnroe (6-7, 6-3, 7-5). During these years, not only did Ashe perform on the court, but he also advocated around the world against any form of discrimination.

In 1979, Ashe suffered from a heart attack and underwent a quadruple bypass operation, and he retired from professional tennis the following year, holding 81 titles. He then became the captain of the U.S. Davis Cup team from 1981 to 1985, but, despite the two titles claimed by his team, he resigned, fed up with McEnroe’s behaviour, combined with Connors’ antics during the 1984 campaign. He was elected to the International Tennis Hall of Fame in 1985.

In 1983, Ashe underwent a second heart surgery, and it was during the recovery that he was likely infected with AIDS during a blood transfusion.

Ashe, who, as a 12-year old, had told his brother he wanted to be “the Jackie Robinson of tennis”, published in 1988 a three-volume book titled A Hard Road to Glory: A History of the African-American Athlete, which he considered as an achievement more important than any of his tennis successes.

The three-time Grand Slam champion kept his disease secret as long as he could but in April 1992, he publicly announced that he was ill with HIV. Less than a year later, on February 6, 1993, he died from pneumonia at the age of 49, leaving the tennis world heartbroken.

“He’s always been for black players someone to look up to and someone who says, ‘You can do it, it doesn’t matter where you come from or how you look,’ ” said Zina Garrison-Jackson – a Wimbledon runner-up who benefitted from one of Arthur Ashe’s programmes, quoted by The New York Times in 1993.

“Arthur showed you what is possible to be accomplished,” she said. “I always wanted to follow in his footsteps, and nobody can forget that he made the footsteps: I can really appreciate the time that he made his breakthrough in. It was harder then for a minority player to break in, especially in our sport, but he did it to the hilt.”

What next: Posthumous award, naming of court at US Open

In 1993, Arthur Ashe was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Bill Clinton.

In 1997, at Flushing Meadows, the new centre court replacing the Louis Armstrong Stadium as the main court of the US Open was named after Arthur Ashe Stadium. Prior to the match, a beautiful dedication ceremony was held with a tribute to Arthur Ashe, in the presence of his widow, Jeanne Moutassamy-Ashe. Whitney Houston was there as a guest star, singing “One moment in time”, in front of 38 former US Open champions.

Besides these honours, Arthur Ashe would be remembered, according to the International Tennis Hall of Fame, as “a man who enjoyed a storied career between the lines and a dignified life as an ambassador of equality and goodwill”.

According to former world No 3, Pam Shriver, “ he was a voice for all the minorities, and that goes for women, too,” she said. “He brought a level of conscience to the game, whether he was speaking on South Africa or inner-city minorities or exclusionary policies anyplace. Arthur’s influence on tennis didn’t fade after he left the sport.”