The ATP, the union which became a Tour; how players took control of world tennis

In the second episode of our trilogy about the roots of tennis’ divided governance, Tennis Majors explains how players took control of the circuit with their union, after a 20-year chaos with concurrent tours. In 1988, players accomplished an authentic coup in the US Open parking lot…

ATP Major Features

ATP Major Features

“A complete mess, a chaotic period.” Tennis thought it had solved its main issue on the governance side by opening to professionalism in 1968. But the way Richard Evans describes the situation for us gives us an idea of the work still to come:

“Tennis organisation from 1968 to 1973 was a jumble of people showing their muscles to get their piece of the cake”, the British reporter, who has covered tennis since the 1960s, sums up. Since the tennis was ‘open’, private sponsors were everywhere and the season schedule had no consistency, aside from the Grand Slams, which followed the same rhythm as today.”

Two competitor tours: the WTC and the Grand Prix

From 1970, two main men’s tours, both of them created before the Open era began, were co-existing :

- The World Tennis Championship (WTC), launched in 1967 by billionaire businessman Lamar Hunt

- The Grand Prix tennis circuit, run by the International Tennis Federation, which also managed the Grand Slam events.

The WTC debuted before the Open era with the “Handsome Eight”; Dennis Ralston, John Newcombe, Tony Roche, Cliff Drysdale, Earl Buchholz, Niki Pilić, Roger Taylor and Pierre Barthès. Then it opened to other players and was holding about 20 tournaments a year by the beginning of the 70s. The WTC was topped with a new-format competition scheduled in May, including the year’s best eight players on the tour.

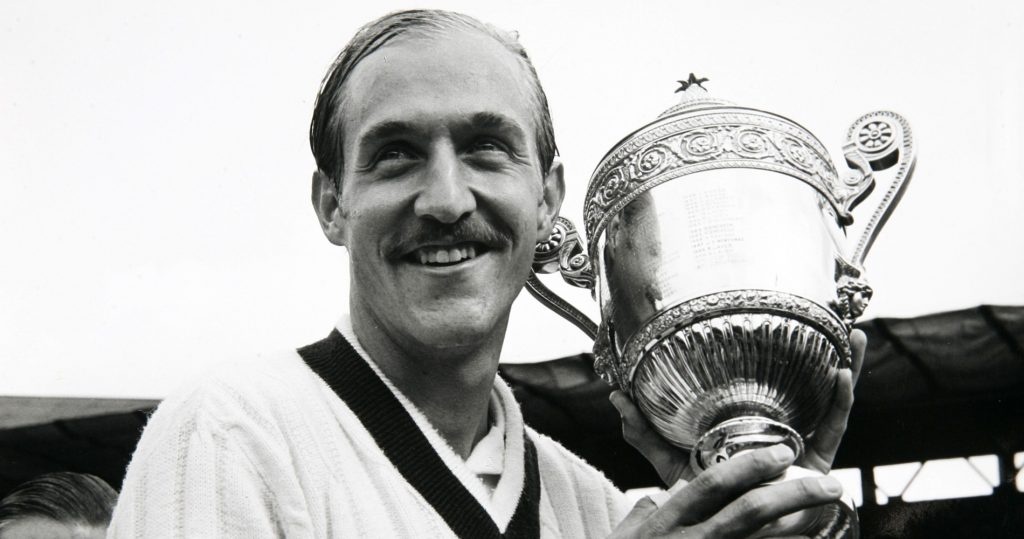

The Grand Prix tennis circuit was created in 1967 thanks to American Jack Kramer, one of the great players of the 40s, who won the US Open in 1946 and 1947 and Wimbledon in 1947. Kramer was a well-known promoter for professional players before the Open era.

“Jack Kramer made a pact with the ITF, that he had fought until then to institute professionalism, Richard Evans analyzes. The WTC caused huge damage to the Grand Prix tennis circuit. Numerous players were sometimes deprived of Grand Slams in reprisals for playing tournaments organised by private sponsors, such as the WTC. Jimmy Connors could not play the 1974 French Open. The French Federation forbade him. He was sanctioned for participating in an intercities tournament in the United States. He had won the three other Grand Slams that year.”

“Allow the players to speak from a single voice”

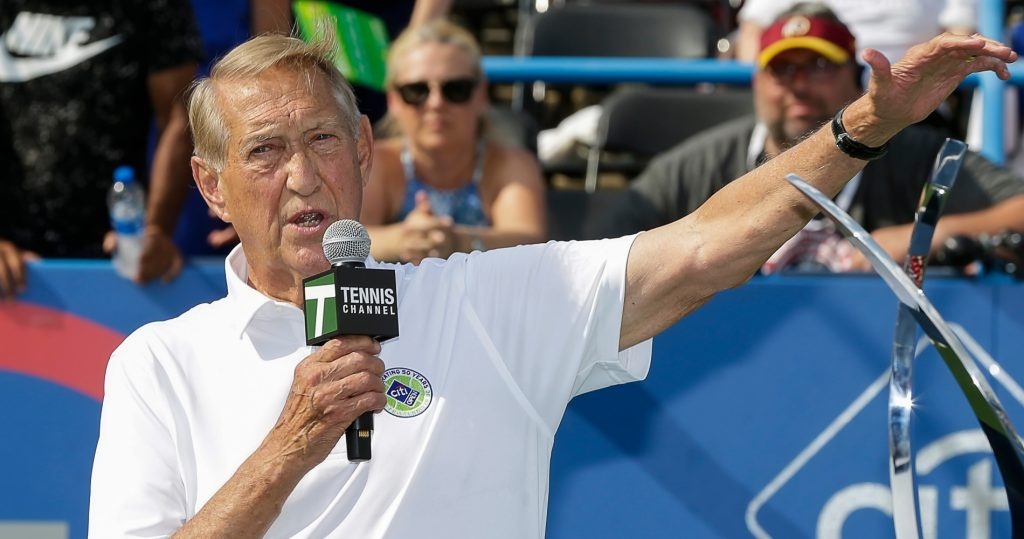

It is in this chaos that the ATP, the Association of Tennis Professionals, was born in 1972. Former player and US Davis Cup captain Donald Dell, also the founder of the Washington tournament, which he still presides over, is one of the three founding fathers. The others are 32 year-old South African player Cliff Drysdale, chosen by players to be their president, and Kramer. He remembers :

“The idea was to create a players’ union, so they could speak from a single voice, to give them more power in the negotiations with tournaments and the International Federation.”

The manoeuvre would soon prove to be really efficient. In 1973, the ITF decided, after the Yugoslavian Tennis federation asked for it, to suspend Niki Pilic for a month, after Pilic’s refusal to play a Davis Cup tie. He was therefore left out of Wimbledon’s draw. The decision was symbolic of the Federations’ control over world tennis. To be able to play a Grand Slam, a player had to follow the rules from his Federation. Reacting to this suspension, 79 ATP players decided to not take part in the Wimbledon event that year, out of solidarity.

“For the only time in history, a healthy title-holder, Stan Smith, didn’t defend his crown in Wimbledon, Donald Dell underlines. That shows the solidarity there was between players.”

Wimbledon’s boycott marked the players’ empowerment in world tennis’ governance. They made the point that they were united, and that if they weren’t playing, there was no tennis. Jan Kodes, a clay-court natural, seized the opportunity to win a third Major title.

“The boycott showed the ATP was well-born, it was its founding act, Dell shouts. We had amazing leaders, among players as well as on top of the ATP with Jack Kramer. Our goal, as ATP leaders, as well as the one of players, was to make the game grow over the years, to defend tennis as a whole, and not just a tournament, a country, a federation.”

The turning point in the US Open car park

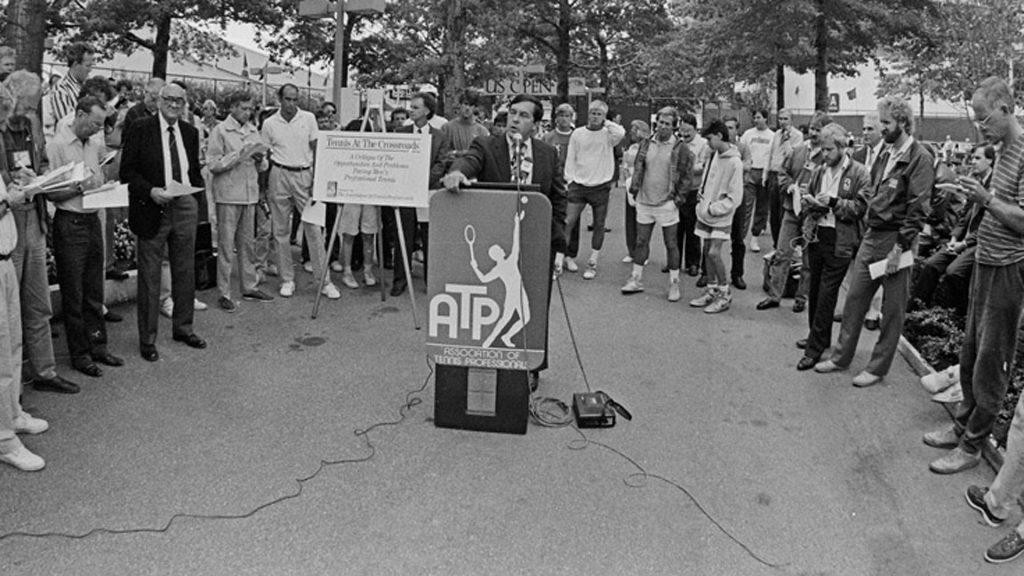

Fifteen years later, a new coup from the players toppled the organisation of the men’s professional tour, by unifying and initiating the end of the WTC and the Grand Prix circuit. It was August 26, 1988, the third day of the US Open. In a parking lot, with a supposedly improvised timing, the ATP CEO Hamilton Jordan called for a press conference. Around him, numerous players were there, in a circle, including Mats Wilander, Brad Gilbert and Yannick Noah. The players’ union boss detailed his “Tennis at the crossroads” plan, in which he was explaining that the ATP intended to create its own tour as soon as 1990.

“All tumbled thanks to Hamilton Jordan extraordinary leadership. This tour, it was his idea”, Donald Dell assures.

Former White House Chief of Staff, Hamilton was a politician of great talent and a brilliant speaker. Ray Moore, ATP CEO from 1983 to 1985, had chosen him to represent the players.

Players had been asking for more money from Grand Slams for several years. But each one refused to do it. They were tired of the dysfunctional governance of the Men’s International Professional Tennis Council (MIPTC), the Grand Prix tennis circuit’s governing body. Players, tournaments and the ITF each had three votes. Therefore the players were in a minority position.

“But things were about to change, then Stan Smith’s and Arthur Ashe’s representative Donald Dell details. We, with the ATP, had won four years earlier a trial against the MIPTC, which wanted to reduce the influence of agents.”

The International Federation and the Grand Slams were taken by surprise.

“The American Federation (USTA) made a mistake refusing to grant Jordan access to a room for his press conference, Richard Evans recalls. By standing in the parking lot, players had five times more coverage than if they had done it in a room. It was the ultimate symbol of the rift between players and the International Federation.”

The International Federation and Grand Slams anyway wanted to keep their independence and didn’t want to join the ATP Tour.

“Since Wimbledon’s boycott, Grand Slams were scared of players and preferred to stay independent from them, Donald Dull justifies. In particular Wimbledon, which always wanted to be on its own”.

The ATP Tour was born with a special governance method. The ATP was legally no longer a players’ union, but a partnership between players and tournaments.

“On the Board of Directors, players have three votes, the tournaments three and the chairman three. The players often are, especially on prize-money matters, in a 3-3 tie with the tournaments. As the chairman doesn’t want to pick a side, afraid that he is to upset the players or the tournaments, the situation is blocked”, Donald Dell analyzes.

From there was born men’s tennis governance as we know it, with the ATP, the ITF and the four Grand Slams as six independent parties, with the WTA making seven.

“This makes decisions and agreements lay on the goodwill of the parties’ presidents. You need leaders”, Dell says.

“We wanted to create Tennis inc”

Richard Evans, who was sometimes more than a journalist for the tennis world, was at the heart of one of the only attempts to let a single body run the entire sport. An old idea that is popping up again during the Covid-19 crisis.

“In 2004, at the initiative of Butch Buchholz – then the Miami Open director- and I, we gathered in Houston all stakeholders from the game to expose our project, during the Masters. We wanted to create Tennis Inc, one single organisation to rule the tennis world, run by a commissioner. Everyone came to that meeting: Grand Slams directors, ATP, WTA and ITF leaders, tournaments directors, tennis industrials, manufacturers. It was impossible to find a common ground. Wimbledon, in particular, did not want to cooperate.

“We called for a second meeting in Miami the following year, Evans who covered more than 170 Grand Slams during his reporting career, says. We invited former US Senate Majority Leader George Mitchell. He had been commissioned by president Bill Clinton to solve the crisis between Ireland, the United Kingdom and Northern Ireland. He had been able to find a solution for the Northern Ireland issue, but he couldn’t do anything to convince tennis’ leaders to work together. That gives you an idea of the magnitude of the problem.”

“Having everybody on its side, it is harmful for tennis’ promotion, Donald Dell, now in charge of tennis for Lagardère Unlimited, judges. Instead of promoting tennis as a sport, in a global market where good marketing is important, and offering a unified product to oppose other sports, the tours and the Grand Slams are defending their own interests.”

For Dell, one of the people who had the most influence on world tennis’ governance, there is still time for tennis to evolve.

“Tennis became a global sport, he explains. Professional players come from several dozen different countries. Before, only a few countries were dominating the game. The Asian market is opening up considerably. But the market is also much more competitive, in the United States for example. You have to unite to promote tennis as a sport, and not defend personal interests.”

To those differences, mostly dating back a half or quarter-century, you have to add the stake of the separation of governing bodies for men’s and women’s tennis. Because men’s tennis grew and made the choice to build itself without considering the women. They caught up step by step. And finally took their revenge.