Roger Federer, the man who reinvented tennis

Roger Federer, who at the age of 41 has just announced the imminent end of his legendary career, has raised tennis to heights that we thought were unattainable

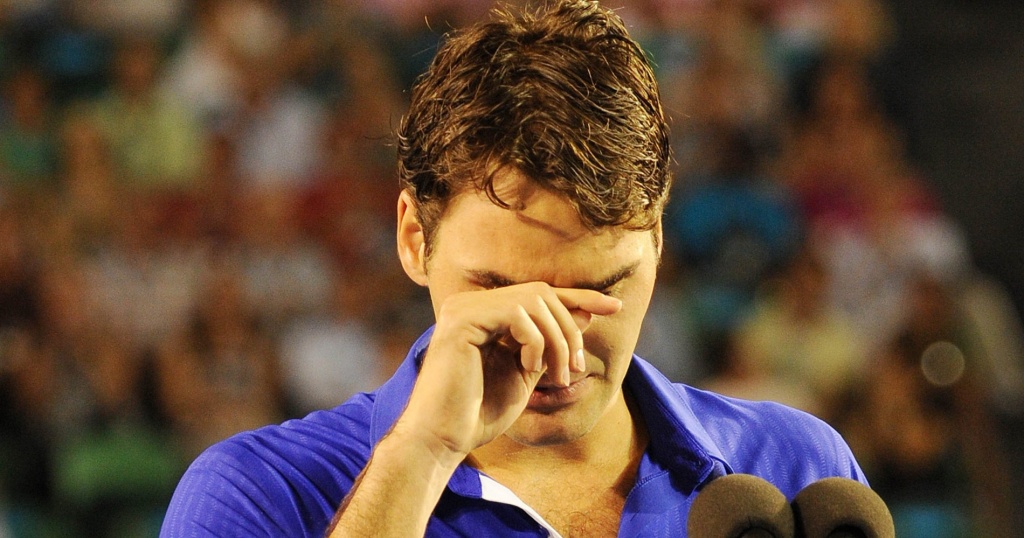

Roger Federer, 2005 | © Alain Mounic / Panoramic

Roger Federer, 2005 | © Alain Mounic / Panoramic

That’s it, it’s over. This Thursday, September 15, 2022 will forever remain a day of infamy in the history of tennis, and sport in general. It’s the day when Roger Federer announced the end of his iconic career; even if it will only really end at the occasion of “his” Laver Cup, next week in London, we all agree that it doesn’t really matter.

And so it’s over. And that’s… bizarre.

Bizarre, and even a little more than that. Roger Federer’s retirement, even if the image might seem violent, is a bit like the passing of a very old relative. We all knew it was imminent, inevitable. But the day it happens, we are all plunged into a deep sadness already tinged with nostalgia, because we all have been in denial about the fact that, deep down, we were not really ready.

No one is ready to face the death of a loved one. No one is ready to face the retirement of Roger Federer.

Federer will embody this era

With the news, a piece of us all, the collective tennis fan, is broken up. Forgive the cliché about “the end of an era”, but it is true that there is a lot of that. The Swiss will remain the embodiment of an era that he helped define with his brilliance, for almost a quarter of a century.

Federer’s career began in 1998, the date of his first match on the ATP Tour, in Gstaad, which resulted in an anecdotal defeat against the Argentinian Arnold Ker, at the not so ready for prime time age of 17 years old. It ended with a defeat in the quarter-finals of Wimbledon, in 2021, at almost 40 years old, against Hubert Hurkacz. Roger Federer would have liked to continue the adventure. But he couldn’t anymore. His body couldn’t anymore.

It’s always like that with tales of sporting greatness. We know how they end, but it is difficult to define precisely when they began. Where to place the beginning of the Federer legend? To the year 1998 and his great debut with the pros, accompanied by a coronation at Wimbledon and a world No. 1 ranking among juniors? To this legendary victory in the form of a transfer of power against Pete Sampras in the round of 16 of the 2001 edition of Wimbledon? At his first Grand Slam coronation two years later, also at Wimbledon, in 2003?

We really do not know. What we notice is that the word Wimbledon comes up often. So we know where.

It is obvious, Wimbledon will remain the tournament most firmly attached to the name. Roger Federer holds the historic record of eight titles there, he wrote the most beautiful pages of his golden book there and reached a never before witnessed level of excellence. Paradoxically, he also had his two most traumatic defeats there, the 2008 final against Rafael Nadal and the 2019 final against Novak Djokovic. Two of the greatest matches of all time, against his two greatest rivals – dramatic moments of the highest magnitude. The last of which one can wonder, moreover, if he ever recovered from it. Not his fans, anyway.

Suddenly Federer started winning everywhere, all the time

Before the advent of those who were to become his two Big Three acolytes, inseparable from his history and its greatness – we will talk about it later – Roger Federer took tennis to heights that we had never seen before. And that, to tell the truth, we did not expect (wrongly) to see each again afterwards.

Of course, pre-Federer tennis had its immense champions, from Tilden to Sampras via Gonzales, Laver, Rosewall, Connors, Borg, McEnroe, Lendl or Agassi, this lofty list far from being exhaustive. But these champions all had more or less a weakness, a blind side, a weaker stroke, a less preferred surface… In short, sometimes they lost.

At his peak, Federer was always hitting the high notes, perpetually, from January to November, on all surfaces. Including on clay, yes, even if it took him a little longer to conquer the Holy Grail of Roland-Garros – not because of a lack of appetite for the terre battue, but because of the hegemony on this surface of the Spanish extra-terrestrial that would later become his foil.

Outside Paris (until 2009), the “prime” Federer won almost everything. He was the first to achieve this total, otherworldly tennis, from one end of the season to the other, with a regal air and absolute dominance. Until touching, at some point, a form of invincibility.

Between 2004 and 2007, Federer won three of the four majors on offer, including twice in a row in 2006 and 2007 (which he remains the only one to have done), winning a total of 41 titles over the course of these four seasons, and competing, at the same time, 10 consecutive major finals. All this while scattering the competition like a puzzle, frustrating the generation of his age (the Hewitts, Roddicks, Safins and co) with the same mastery that he had extinguished the generation before him.

Some will say that Federer is also the product of his time, that he took advantage of the contemporary homogenization of surfaces to establish this reign without sharing. On the contrary he may have been one of the victims of the general surface slowdown, in particular that of the grass. He too had to adapt to his game style to gradually move, while smoothing the contours of his aggressive game, from a flamboyant attacker to an “all around player” in style, will and physical condition. suitable for any pace of play.

In the heart of the 2000s, tennis could just as well have been played on pre-2000s grass, har-tru clay, ice or crushed cow dung – nothing would have changed. At that time in his career, Roger Federer was not winning thanks to the surface, he was winning simply because he had no more flaws, in the technical the tactical or the emotional aspects of his game.

And even less on the technical level, even if some went to look for it on its sometimes fragile backhand, when it came to playing it from a certain height. Until he worked on it and revolutionized it, too.

Sampras’ record

Over the course of his unparalleled exploits, the Basel native, perhaps in spite of himself, sparked a mad race for records which would eventually entice a Grand Slam vertigo of sorts. It was uncontrollable once Nadal and then Djokovic entered the dance. In 2009, it was when his period of ultra-dominance had also begun to fade – notably to the benefit of the Spaniard – that Federer, paradoxically, definitively entered the pantheon by finally winning, at Roland-Garros, the only Grand Slam that still eluded him.

Then by winning his 15th Grand Slam title at Wimbledon to beat Pete Sampras’ record. A record that we thought was unattainable, and which would end up lasting barely seven years.

It was at this precise moment, perhaps, that tennis shifted for good into another dimension. A dimension in which the protagonists came to baffle us, spoil us and redefine everything we thought we knew about what was possible in our sport. The race for the number of Grand Slam titles, and even more the race for the GOAT, the famous Greatest of All Time, not many people cared about it before Federer. The Swiss didn’t just take tennis into the 2.0 era. It also led him straight into the lair of the queen of statistics.

Of course, Federer didn’t do it alone. He did it with the help of the two phenoms who had the impudence to look him in the eye, Rafael Nadal and Novak Djokovic. It is strange, moreover, to think that the two greatest rivals of Federer’s career were born long after him, and reached their own unbeatable stages long after that of the Swiss maestro. This age difference – 5 year for Nadal, 6 years for Djokovic – probably did not help him in his head-to-head with these two champions, who are both unfavorable to him. But this is another debate for another time.

What we can say without too much risk of being wrong, on the other hand, is that without Roger Federer, there would have been no Rafael Nadal, nor Novak Djokovic. Nor perhaps today, by extension, Carlos Alcaraz, who is for many the perfect synthesis of these three monsters. Roger raised the tennis bar so high that Rafa and then Novak in turn had to raise their level of play to heights they perhaps did not even suspect, just to be able to exist. Would they have had the same requirement towards them without their eldest? The same appetite for victories? It is permissible to doubt it.

2017 – 2019 – The ultimate pleasant surprise

Still, when the Spaniard and the Serb took command of world tennis at the start of the 2010s, the Swiss showed another form of greatness. In his thirties, he could have left the stage, as a fallen monarch, sated with glory and money. On the contrary, he chose to reinvent himself and rose from his ashes, despite the mind-bending strength of the competition (we do not forget Andy Murray or the notion of the Big Four which prevailed for a long time), despite the inevitable physical problems which began to take hold of his body, especially the back, in 2013, then those damn knees, from 2016.

From this splendid burst of pride, two unforgettable “revivals” were born. The first in 2012 (more than ten years ago, yes…), with a 7th title at Wimbledon won after more than two years of drought in the Grand Slam. And especially that of 2017 and an unforgettable coronation at the Australian Open, after six months of absence, after a tense, dramatic and unexpectedly successful final against Rafael Nadal, who was also just emerging from the shadows of injury.

Then began the final enchanted sidebar of Roger Federer, who found, beyond the age of 35, the flame of his youth. He took the opportunity to reel off, during this same year 2017, a record eighth Wimbledon for the road. Then for a final, tear-inducing act of brilliance, Federer flew to a 20th and last Grand Slam title, won at the 2018 Australian Open, and became the oldest world No 1 in history at over 36 years old.

Knowing that Carlos Alcaraz has just become the youngest, the circle is complete, in the most perfect way.

Still, the Federer legend seemed endless. In 2019, the Basel phoenix rounded off his statistics: 100th ATP title won in Dubai, 10th title won in Halle (his personal best), 100th match won at Wimbledon in the quarter-finals against Kei Nishikori. And then, four days later, there was this devilish final against Djokovic. Then the knee, again. Then Covid. Then the knee, again. And then Father Time, quite simply, finished the job. Legends never die, it’s true. But they end up resting one day.

Today, Roger Federer is leaving and the indelible mark leaves on the history of our sport is immense, like the deep void he has etched into the hearts of his legions of fans.

Is he the GOAT? No one knows. At the end of the day, he may not have been the best in the history of the game since most of the numbers are against him, now that Nadal and Djokovic have broken his record for Grand Slam titles. But he may well have been the greatest, yes, if we refer to the emotion aroused in the hearts of the public.

Where does this emotion come from? Perhaps, later on, to a form of empathy linked to the way in which his two rivals martyred him and often brought him back to the reality of his age. But it’s probably deeper than that. It also comes from the beauty of the artistry that Federer’s game possessed, this unequaled elegance born of absolutely prodigious muscular fluidity and eye-hand coordination.

Roger Federer has never sacrificed aesthetics on the altar of efficiency, even if it means giving tennis the false image of an easy sport. All without ever, or very rarely, giving in to the temptation of the easy, indolent blow. This alliance of pure poetry and bloodlust, which we perhaps found in a Zinedine Zidane in soccer or a Michael Jordan in basketball, is something we had perhaps never seen on a tennis court.

A God of tennis but with such a human sensitivity

We could of course also speak of the polite character of Federer: extremely courteous, perfect communicator, handling languages with dexterity, he was always generous with his words and time. This has undoubtedly largely contributed to his universality, even if it also caused some “enmity” with those who preferred the insolent rage of a Djokovic or the muscular aggressiveness of a Nadal. But deep down, we wonder if, where Federer managed to move so many people, even more than with his talent, it is not rather with his weaknesses.

A God of tennis but with such a human sensitivity, “Roger” had this unique gift of making his genius accessible to as many people as possible. He touched people in the heart with his tears spilled on the biggest stages of the world, and not only once, even if the most famous will perhaps remain those which flowed from his face after his defeat to Nadal in the final of the 2009 Australian Open.

He was vulnerable. He was heartbroken. He gave everything to tennis and everything to the fans.

Yes, maybe that’s it. Over the course of his victories and painful defeats, Roger Federer was able to prove that he was not just an inaccessible star, but above all a man, reminded of the harsh reality of passing time and the effect it had on his aging body.

Such an abnormal end, for such a divine champion. All Roger Federer, in the end.

Federer never retired from a match, and he played his very dominant game years without resorting to medical or other forms of treatments to enhance his “wiinability quotient”. He simply soared once he achieved his

During his years ot dominanation Federer maintained his #1 at an unbroken number of weeks ithout stepping back from that ranking. It is an unmatched achievement. He never retired from a match, and competed without medical or other intervention and fully participated in the tournament roster without extensive withdrawals from the tour.. He never referred to an ailment or injury as the reason for a loss. He inspired others to spend a lot of time and effort for years to try to match his skills in shot-making, precision serving, and the always courageous attacking game that was his hallmark. He was the first to achieve the high count grand slam titles, and catching up to him, then passing him, came only after he’d had three operations on his knee, and did not play the complement of ATP tournaments. Remember that: only after he encountered serious problems with his knee did the other two eventually catch up, and then pass him. That shows that Federer was the most dominant player, including dominant over his two main rivals. It is Federer the Great, the way it was Alexander the Great in terms of achievement.