Michael Downey interview: From Brett and Borfiga to the indoor tennis centre, how Canadian tennis found a winning culture

As he prepares to step down as CEO of Tennis Canada, Downey tells Tennis Majors why he is most proud of creating a renaissance in high performance in the country

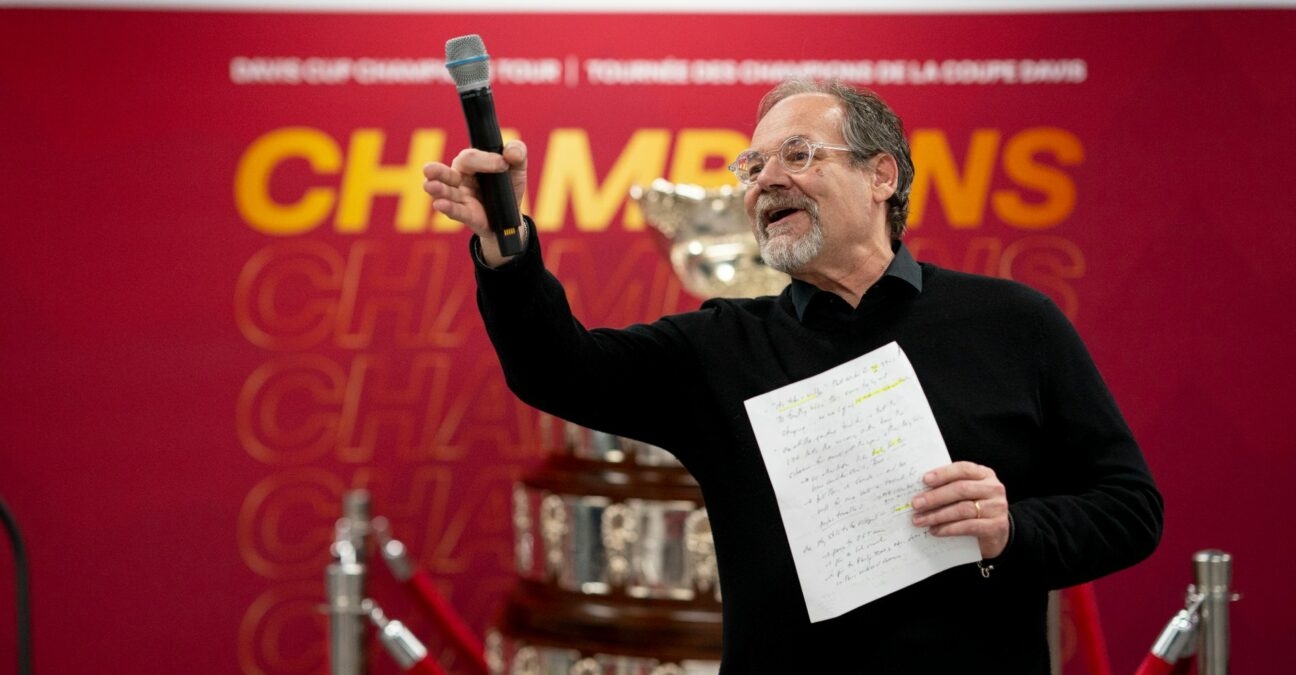

Michael Downey – © Peter Power

Michael Downey – © Peter Power

Systems, they say, do not create champions. Recent history would suggest this is true; look at Novak Djokovic, Serena and Venus Williams, Andy Murray, for example, who all grew up largely outside of any funding from their national associations.

But a good system, run by the right people, with good coaches and good facilities can make it more likely that players will break through.

Michael Downey steps down as president and CEO of Tennis Canada at the end of December, having been in charge across 17 years, first from 2004 to 2013 and then, after five years at the LTA in the UK, from 2017 to 2023. He leaves with Canada as Billie Jean King Cup champions and with the men’s team having been recently ranked No 1, having won the Davis Cup in 2022. And, crucially, having overseen a period in which Canada, thanks to Bianca Andreescu’s stunning triumph at the US Open in 2019, had a Grand Slam champion in singles.

Until Downey took over, Canadian success had been confined to doubles, with the likes of Daniel Nestor and Sebastien Lareau rare winners. But Downey had lofty goals. While increasing participation was important, he wanted to lift a nation who had not had a top-100 singles player, in the men’s or women’s game, for seven years, so he focused on high performance.

“I think it started with first of all, making a commitment,” Downey told Tennis Majors. ” We were pretty poor at it, let’s be serious. We put on two phenomenal tournaments, in Toronto, Montreal…we had gone something like seven years without a top 100-ranked singles player. And the press here used to say, you just waste your wild cards at the Masters level, because the Canadians never get past the first round.”

Borfiga and Brett the key personnel

Tennis Canada invested heavily; in a national tennis centre, which opened in 2007, and in coaches, with Bob Brett and Louis Borfega proving to be the perfect combination.

“We like to say we went out for one and we came back with two,” Downey said. “We wanted an international person to be our head of high performance. And the guy that we were highest on was a guy named Louis Borfiga, who had run the French Federation’s main centre in Paris for kids.”

Looking for a high-profile coach, Downey approached Brad Gilbert, the former world No 4, who had helped Andre Agassi to world No 1 and later had spells with Andy Roddick and Andy Murray, before most recently joining the team of Coco Gauff, with instant success as she won the US Open in 2023. “He didn’t even know who I was,” Downey said. “(But) I reached out to Brad and said this is what we’re trying to do.”

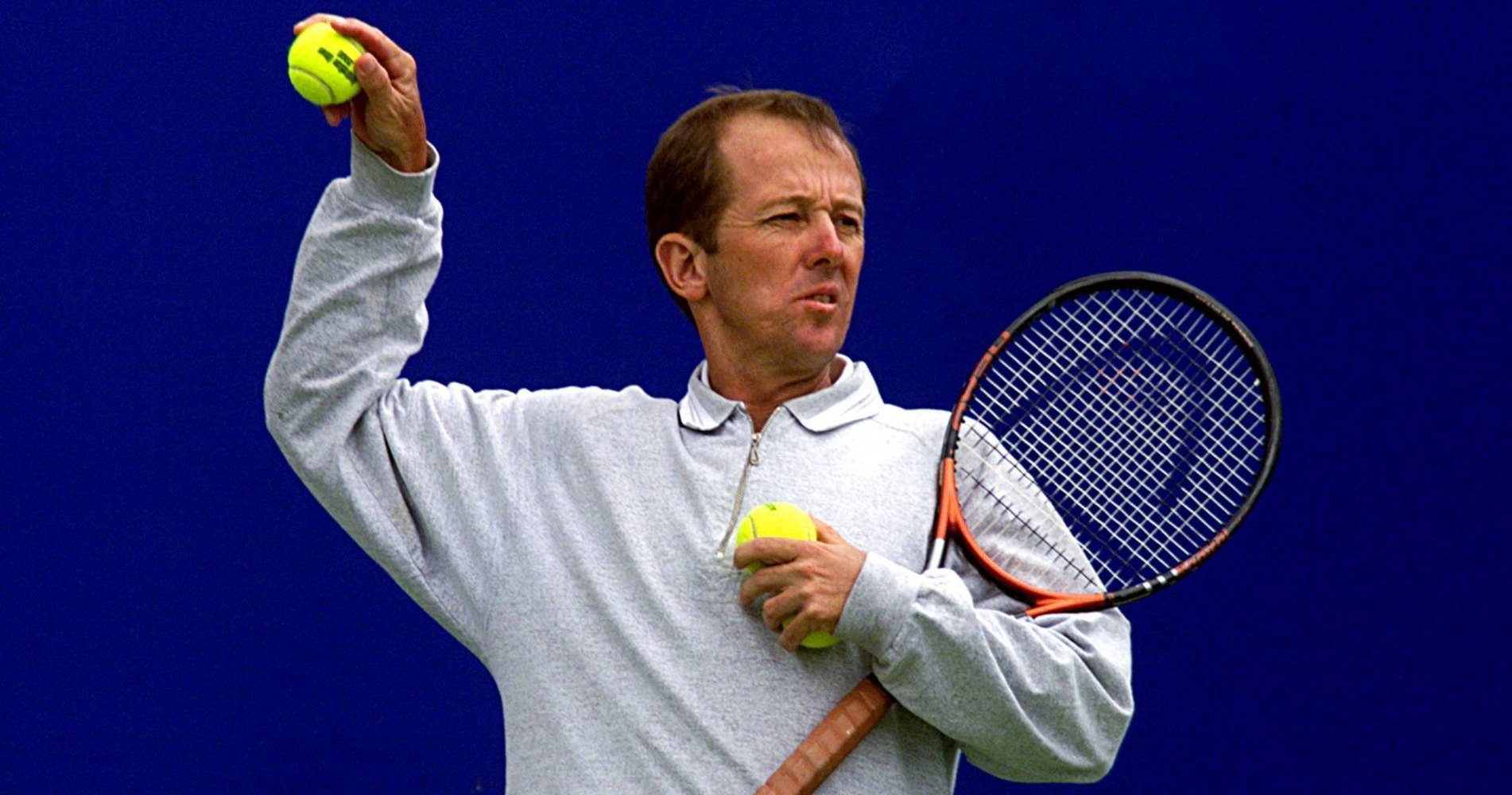

Gilbert recommended Bob Brett, the Australian who had coached Boris Becker, Goran Ivanisevic and many others, but didn’t think he would work for a federation. Downey “chased” Brett and invited him to visit.

“He said, ‘I’ll give you a weekend of my time, but I need to meet you, I need to meet your head of high performance, I need to see the facilities and we’ll talk’,” Downey explained. “At the end of that weekend, Bob said to me, ‘I don’t want a full-time job. I don’t want to be your head of high performance. But I’ll give you a contract, if your new head of performance (Borfiga) wants me. And I want to work on the younger kids, and I want to help get sports science done. So we had Louis Borfiga coming in as the head and we had Bob Brett.”

Interestingly, Downey said Borfiga and Brett didn’t actually strike up much of a rapport, personally, but their presence was vital.

“The truth of the story is they didn’t necessarily get along,” Downey said. “Because one was a system guy and one was an independent coach. But I honestly believe we were better off because of the conflict. I think we actually made better decisions because Louis was looking at it from a system (point of view) and Bob was saying, ‘Well, you know, you’ve got to have customisation, not all kids want to go to Montreal’, all this kind of stuff. I think it created a shitload of work for me and another guy in high performance. But in the end, the conflict made us better.”

No culture of winning

They might not have been best buddies, but Borfiga and Brett agreed on one thing. One very important thing.

“Both of those guys, when they joined, said, ‘You have no culture of winning here, people just want to get a player to the top 100. That’s not winning.’ So they really brought a culture of winning.

“They also wanted to change the high performance coach certification program, because they said, these are your future Canadian high performance coaches and we want it more practical. Both of those guys did modules to help with the training of future coaches in this country at the highest level. It was all about practicality and it was all about what it takes to win. Those guys made a big difference in how do you get the win and developing the coaches to believe in winning and the players to believe in winning.”

National tennis centre

Timing is everything. Downey likes the saying: “luck is when opportunity meets preparation”. “I think in the end, the preparation was the commitment to build a national tennis centre – we had never had anything like that before – and also to build regional programs.”

The National Tennis Centre opened in 2007. At that time, Milos Raonic, who would go on to reach the Wimbledon final in 2016 and has been ranked as high as No 3, was a teenager, planning to go to university in the United States. Genie Bouchard, who reached the Wimbledon final in 2011, was two years younger.

“The opportunity was that Milos, who was 17 at the time and headed to University of Virginia on scholarship, actually became the first entry into our national tennis centre because he met a guy named Guillaume Marx, whom Louis Borfiga had hired from the French Federation. And I think that was a bit lucky. If we hadn’t had the Montreal NTC, and we hadn’t had hired Guillaume, then Milos would have gone to Virginia.

“The same with Genie, Genie was 15, I think, and she was training in the US. And I think it gave her family an opportunity to move back to Montreal, where the family was, probably save some money, quite frankly.

“So these were opportunities that we took advantage of, because we started a national tennis centre and got serious. And I think that the luck was they broke through early. I still remember someone telling me, it’s gonna be a decade plus before you see great results, but I think Milos and Genie got us there faster, but they wouldn’t have come if we hadn’t built a programme.”

Tennis Canada also realised they needed to be flexible. When Borfiga told Downey that they didn’t have enough strength at the National Tennis Centre to give Raonic the competition he needed, they paid for him to go to Spain to train with coach Galo Blanco. Not only did that move help Raonic make a major breakthrough soon after, qualifying and making the last 16 at the Australian Open, he also saw the work ethic in Spain.

“I had breakfast with him before the new year,” Downey said, of the 2010 off-season. “And I said, ‘What’s the difference in Spain versus Canada?’ He said: ‘Well, in Canada, you guys just talk about getting somebody to the top 100. In Spain it’s all about beating Rafa’. Not all players can make that move. But I think these were some improvisations, we took a system but then we said we got to improvise, because each one of these kids is slightly different.”

Andreescu’s US Open win an inspiration to everyone

The success of Raonic and Bouchard, in particular, helped give Tennis Canada some breathing space. And their success inspired others. When Raonic was reaching the Wimbledon final in 2016, Denis Shapovalov was winning the junior title; Bouchard’s success inspired the likes of Bianca Andreescu and Leylah Fernandez to break through.

“You’ve got to remember, in our country, we’d never had a singles player get to a final of a Grand Slam, so our standard was lower,” he said. “It started with Genie, and then Milos….but Bianca went one obvious step further, in that she won. It’s one thing to get to a final and lose, but she actually got through and how she got through, to beat Serena (Williams), the way she did in front of 24,000 people when Serena was going for No 24, and she had a 5-1 lead and then she lost it and then she still won….

“It’s not just that she won, it’s how she won. I will tell you, we did tracking and 35 percent of the country was following her when she won the US Open. Those are Wayne Gretzky-type hockey numbers in this country, one in three Canadians was actually following her when she won the US Open and eight million Canadians actually watched the final. That’s gold medal hockey type levels.”

In his time at the LTA, Andy Murray won Wimbledon for a second time and Britain won the Davis Cup (in 2015). Downey doesn’t take credit for either but looking back, he said the focus on Wimbledon, for young players, was all-encompassing.

“When I was there, the thing I picked up very early on, is the kids aspired to play Wimbledon,” he said. “What they wanted to do more than anything else was play Wimbledon. But, you know, if you get a wild card from Wimbledon, you might (only) be 200 in the world, 250 in the world.

“So I think I give the credit to Scott (Lloyd, the CEO) now. And I think it’s Michael (Bourne), who runs the high performance…they’ve been able to move the goalposts. I think that was part of the problem that a lot of British players, not all of them, but a lot of the British players were like, ‘my Mecca is to play at Wimbledon’. Is that phenomenal? Yes. But at the end of the day, I don’t think that was Andy Murray’s only goal.”

Future of Canadian tennis

Downey leaves his role with just two women – Leylah Fernandez, Bianca Andreescu – and one man – Felix Auger-Aliassime in the top 100. All three of those players have been hit by injuries, as has Denis Shapovalov. If all of them can get back to and maintain full fitness, though, the talent is there for future success, while the performances of 18-year-old Marina Stakusic, who helped Canada win the Billie Jean King Cup, offers promise for the future.

Downey believes all of them can achieve big things, even if he agrees that, so far, they have not achieved what they might have expected to. “I think they would say the same of themselves,” he said. “They’ve done better than any Canadians before them, ranking wise in singles. But other than Bianca, she’s the only one that’s actually won a Grand Slam yet. And I think the Felixes and the Leylahs and the Denises would be sitting back saying, this is what I still want, but they know how darned difficult it is they think.

“The advantage is, let’s be serious, they’re still young kids, like they’re still young kids. You know, they’re all under 23 years of age, I believe. So there’s still a lifetime of tennis ahead of them in terms of being able to break through. But I think in the end, this is the pack mentality, the fact that Bianca won, it is not only good for the country, and good for Bianca, it raises the bar for the rest of them to say, well, she’s got something I don’t have yet. I still haven’t won the big enchilada. And so I think it’s gonna drive them.

“It’s all about step functions; get players into the top 100, get them that they truly believe they can get into the top 10. They get into the top 10, they start winning some tournaments. And then the next one is how do you get over that hump? I think us winning Davis Cup last year was one hump. I think the Billie Jean King Cup, like I think Leylah and Marina will take that win and it will propel them next year.”

Most proud of high performance focus

Downey says he’s proudest of “a renaissance of high performance” but even he can’t quite believe the success that has happened under his watch.

“Really, who would have thought that in ’19, Andreescu would win the US Open, that the boys would make the finals in Davis Cup. In ’21, Leylah loses to your Brit (Emma Raducanu) in the final at the US Open. The boys win the Davis Cup in ’22, the women win the Billie Jean King Cup in ’23 and then all along you’ve got Milos losing the final at Wimbledon, Genie losing the final, like these kind of results were just not on the radar back in 2006 and 07 when we started the journey.

“What it’s also done is, I like to say the bar has been raised in this country, not just for Tennis Canada, but for independent coaches and academies because they kind of know, wow, Canadians have broken through, so the bar is higher. I think the influence of Tennis Canada, in influencing the wider ecosystem in Canada has been a big part of this.

“That’s what I’m most proud of, is what these players have done when they got a little more support, but they believe themselves in that end. It’s had a great fringe (benefit). I think we’re proud that we’re getting more indoor courts. High performance success actually helps other aspects of growing the game, because it gets us to the dialogue. Because tennis historically wasn’t in the dialogue with a lot of these municipalities, they just thought of it as a summer sport. Now they want to talk about year-round courts, because they all want a Bianca or Leylah or a Denis.”

Tennis an inspiration to other Canadian sports

Such has been the success of Tennis Canada that other sports have come to them to ask their advice when trying to improve their high performance levels.

“Through the years, we’ve had a lot of questions from other national governing bodies about your High Performance Strategy,” he says. “What did it take to make the change? What they wanted to understand was what were the steps. A lot of it was raising money and leveraging that money in a successful way. But it was about a president or a chair sticking to the strategy. These bodies get new leaders all the time. And we were lucky that we had chairs that said, I’m on it, I’m not out to change it, what do you need to make it better?

“Alpine Skiing was actually one, I know the CEO, she reached out and wanted to understand the strategy, because her board really wanted more excellence. There was a takeover of that board because they hadn’t been developing champions.”

Downey said he would still be on hand to help the new CEO and chairman, Gavin Ziv, but he says he has no regrets about his decision to stand down.

“Oh no. I’m going to be 67 in June. When I left Britain, I thought I might do it for three or four years, I’ve ended up doing it for six and a half years, I went through COVID. We had to lay off 40 percent of our staff. These things take a toll on you.

“And I also believe that people in these jobs sometimes stay too long. And even though I’ve got a lot of energy, you got to have this fight. I’m also one that believes change is good. I’m better to leave before my best before date. I couldn’t have scripted it any better, oh my god. No, it is fine. It is time.”