Eric Hernandez, the physical trainer who turned Daniil Medvedev into a “non-violent steamroller”

Hernandez accompanies Daniil Medvedev on the Tour when Gilles Cervara is absent, like this week in Los Cabos. A key man in the world No 1’s team

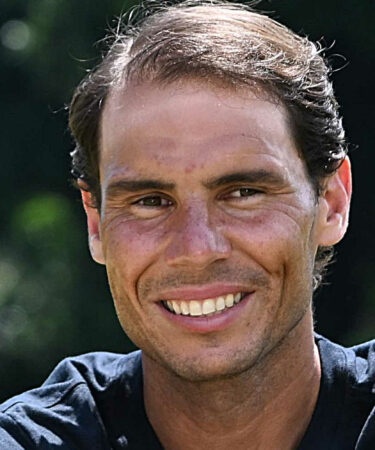

Daniil Medvedev and Eric Hernandez practicing at the Mouratoglou Academy, May 2022 | © Tennis Majors

Daniil Medvedev and Eric Hernandez practicing at the Mouratoglou Academy, May 2022 | © Tennis Majors

It’s a ritual after every session. Even the heavy ones. Daniil Medvedev, exhausted by the heat of the Côte d’Azur (he trains at the Mouratoglou Academy) would have good reason to rush to the shower and the physio after three and a half hours of effort, worthy of a five-set match.

But the Russian always takes five minutes to feed the relationship with his physical trainer, Frenchman Eric Hernandez, by challenging him to a game of skill. It’s a kind of petanque with a tennis ball. The two men stand near the net with their backs to him and gently drop the felt ball to roll it to a stop as close as possible to the baseline. Karen Khachanov is said to be the best at this game on the circuit. Medvedev, a competitor at heart, has promised to challenge him and Hernandez is his sparring partner.

To the next rally, won by Medvedev…

A few minutes earlier, the Russian was smiling less on the court. At the end of the session, in particular, he had done the famous exercise that makes you feel sore just watching him. Medvedev has to sweep the baseline from left to right, as if he were being swept by an opponent. He runs without playing tennis, but he has to catch and return a 650-gram medicine ball, handed out by Hernandez in a random, and often court-covering, manner. Four times, five times, sometimes eight, Medvedev plays the Sisyphus of the courts, before grabbing his racquet from the ground and playing the point with his training partner.

The next time you see Medvedev emerge victorious from an intense 10-plus shot rally, you can tell yourself that there is no miracle.

Eric Hernandez has been a member of the world No 1’s team for almost 10 years. He is present on the court at almost every training session, with the head coach and performance manager Gilles Cervara. “It’s a strength to work in pairs,” says Hernandez, 37, who was born in Foix, in the south-west of France, but considers himself a native of the Côte d’Azur, having settled there 25 years ago.

“A physical trainer who stays in his fitness centre cannot be sufficiently in touch with the player’s performance. When we work on certain movements, it’s very important that I can watch how it happens. The tennis and physical objectives are very often mixed in the sessions. Gilles was asking for it. So was I.”

The Medvedev – Cervara – Hernandez trio was formed in Cannes in June 2014. The Russian was then a gangly teenager on the junior circuit just arriving in France to shape his tennis. He was being monitored collectively by the academy’s technical staff – including Cervara and Hernandez, with Julien Jeanpierre and Jean-René Lisnard also around.

Hernandez was “a footballer at heart”

The physical trainer, then at the beginning of his career, came to tennis almost by chance. With a degree in sports engineering, physical preparation and sports management, he was a “footballer” at heart. Hernandez played at the highest level of amateur soccer in France, under the colours of Fréjus, where French international Adil Rami – also famous for a recent relationship with Pamela Anderson – was one of his partners in defence.

“But where others like him managed to branch off into a professional career, I was injured when the training rhythm went to two sessions a day – for reasons that today I am able to understand.”

At first he tried to join a club but football was a closed environment. “If someone had told me at the time that I would make a career in tennis, I wouldn’t have believed it. Nadal at the French Open was all I knew.”

But a door opened at the Monegasque tennis federation. “At that time, I didn’t know tennis but I knew how to analyse an activity. I seized the opportunity and I would do all my training there.” With the man who trusted him, Fabien Lefaucheux, he set up a company and soon obtained contracts in other activities such as regional cycling, handibasket, individual training of certain footballers and rugby players before committing himself to the Elite Tennis Centre in Cannes.

If someone had told me at the time that I would make a career in tennis, I wouldn’t have believed it. Nadal at the French Open was all I knew.

Eric Hernandez

At the end of 2017, Medvedev asked Cervara to become his full-time coach. A true performance manager for the Russian, the French coach, who also comes from the region, had carte blanche to organise a team around him. Cervara himself is well informed and trained in the subject of physical preparation and needed a partner who is both competent and open to the innovations that he will want to propose. Hernandez had the profile and would stay around, increasing his presence.

“Today, in my professional life, Danill is my priority,” says Hernandez. “I owe him 25 weeks a year.”

The rest of his time is taken up with other activities with his company BFS Training (as in “Better Faster Stronger”), including being the manager of physical preparation for Thierry Ascione and Jo-Wilfried Tsonga’s All’In Academy, and the launch of an academy (TAG Tennis) in Melissa, NE of Dallas in the United States, with former Belgian player Sebastien Leitz.

The year of 2017 was also when Medvedev changed gear with physical preparation. He stopped seeing it as a boring constraint and understood that he needed to build a competitor’s body. Tall (1.98m) and slim (83kg today according to the ATP), Medvedev had neither the natural physique of an imposing tennis player, nor the approach that encouraged him to build a body.

“Daniil has always kept a desire to work, he has never cut a session for me,” he says. “But before 2017, it was not easy because he was reluctant to work. He found it hard, he had never trained in a very structured way, his lifestyle was that of a young player who didn’t forbid himself to go out. He did the physical training because everyone in tennis trains physically, but you could sense that he was wondering where the need was.”

If I ever play a Grand Slam quarter-final, it will be really big

Daniil Medvedev quotes by Eric Hernandez

Medvedev was far from being a number one on the rise. “I remember sessions where he was looking at posters in the gym. He would look at, say, Federer, and think openly, ‘If I ever play a Grand Slam quarter-final, it will be really big,'” Hernandez smiles.

“So the cost-benefit ratio was not obvious to him. He didn’t quite understand what he was doing. But with Gilles, we wanted him to understand.”

At the end of 2016, a few numbers help him understand: Medvedev went from 329th to 99th in the ATP. The man who could hardly see his way out of the Futures and Challengers understood that he would be able to make a living from tennis and that a change of approach in his preparation could change everything.

At this time, Medvedev was still injured a lot. He felt his body was fragile and feared he would explode if he multiplied the loads. Cervara ended up obtaining the opposite reasoning: the player must do violence to build a body without which his natural qualities of displacement and competitor will peak at a low level. “From that point on,” Hernandez recalls, “he was able to say to himself: if I have to do a four-hour session today, I’m going to do it.”

Putting sporting knowledge into tennis practice

Hernandez was then able to put into practice his idea of physical training applied to tennis. “Coming from other sports, I consider tennis to be a sport of the legs,” he says. “In tennis, you have 300 grams in your hands, there is a projectile that you have to send back with a great deal of leverage. The acceleration and release of the upper body counts more than the strength. There is hardly any difference in the quality of the ball strike between the 50th and 250th in the world. The difference is elsewhere. Tactics and mentality perhaps, but also the physical aspect, the physical aspect in the lower body. In tennis, you have to be anchored to the ground, optimise movement in space and pelvic rotation, be able to move well and above all have the strength and endurance to repeat these movements efficiently and limit the risk of injury. So the priority is to build your lower body on all the muscle groups.

Coming from other sports, I consider tennis to be a sport of the legs

Eric Hernandez

“Daniil,” Hernandez continues, “does not have a natural strength quality. When we started working with him, he was already moving very well and had good coordination. We could improve that, but above all we had to make him stronger to repeat the efforts. Especially as he runs a bit more than the others because of his backward position on the return.”

In 2017, despite injuries, Medvedev moved up 35 places in the rankings. In 2018, he entered the top 20. This building phase ended in 2019. When Medvedev has changed shape, he achieves that crazy summer that takes him to the final in Washington and Montreal, then to victory in Cincinnati, then to the US Open final and soon to the top 5.

Weight training is still the mainstay of Daniil’s preparation. “It almost half his job,” says Hernandez. “It’s a classic case with tall, thin players: he loses tone if he doesn’t train, and then he’s not the same player. When he puts in a string of good performances in tournaments, paradoxically he gets out of training and I have to call him back. It’s not uncommon to do physical training during tournaments, even Grand Slams. When you win 6-2, 6-2, not much happens physically. One year he played 23 matches in 33 days. He lost muscle at the end. We know you can’t go more than ‘so long’ without a physical session.

When he puts in a string of good performances in tournaments, paradoxically I have to call him back. It’s not uncommon to do physical training during tournaments, even Grand Slams. When you win 6-2, 6-2, not much happens physically.

Eric Hernandez

“His training volume now means he’s totally in there. If he is not injured, he will have loads that correspond to the big games twice a week. The sessions are often long, but they match the level of ambition of the project. If one day Daniil finds himself under stress in a hard and long match, he won’t be able to respond in the right way if he hasn’t experienced that in training. Today Daniil has five hours of intense work a day, in two blocks. With Gilles, we have managed to get him into this regularity. Daniil is one of the 10 or 15 players in the world who work the hardest, that’s obvious. And when you see the result, it’s fabulous. He is a kind of steamroller who is not very violent. He won’t crack first, he’s armed to do a lot of things and not many events can put him in a critical situation.”

Cramps in Miami in 2021? “You never know what stress can do to a player,” smiled Hernandez. This morning’s practice was more physically demanding than any three-set match.”

Daniil is one of the 10 to 15 players in the world who work the hardest, it’s clear.

Eric Hernandez

The challenge is all the greater because Medvedev plays so much. In 2021, he chose to play the ATP Cup, the Olympic Games, and the Davis Cup in addition to his normal schedule. As well as his Masters 1000 commitments, he often drops down to play ATP 250s and 500s to challenge Djokovic and Nadal in the rankings, to good effect, since he’s the world No 1.

He had only three weeks between the last competition of 2021 and departure for Australia, both to rest and to start preparing.

“What counts,” says Hernandez, “is to have a few recovery periods during the season and to listen to him when he says he feels tired or when we see that the day’s load is weighing on him. People often make winter preparation a big deal but… you don’t build your season on three weeks of physical training in December. If he hadn’t had his inguinal hernia operation in April, we would have given him a rest period, for example.”

The suspension from Wimbledon also acted as a window of opportunity. Medvedev took a few days off and had a two-to-three-week head start on his rivals in terms of hard court preparation. Medvedev, Cervara and Hernandez are keen to see the result in the short term. “Yes, he played a good match,” Hernandez told us from Mexico after the first round in Los Cabos, where he is with Medvedev. “But this is the first of 21 that we need to win this summer.”

Nineteen to go.