Anna Kournikova: The end of the road in Charlottesville, and how the Russian started again

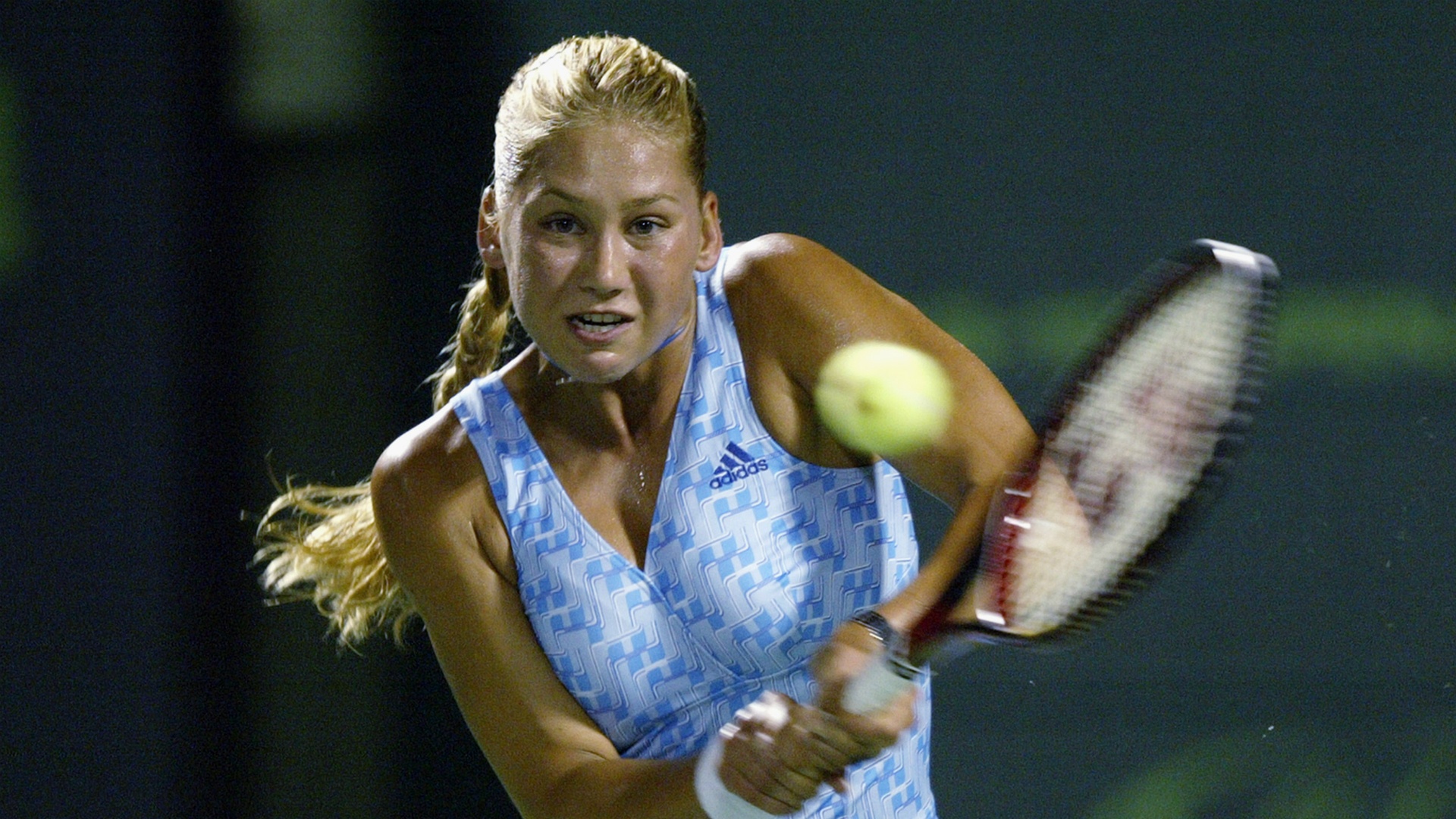

Anna Kournikova cracked the WTA top 10, reached a Wimbledon semi-final and won grand slam doubles titles, but she is portrayed as a failure.

By the time Anna Kournikova played her final tour match, vultures were already picking at the bones of a once-feted great tennis talent.

Many were leching over those same bones, of course, while glorying in her downfall. Picking out the young Russian as prime schadenfreude fodder while sleazily sparing as much thought for her physical form as her tennis form.

When the veteran Daily Progress sports writer Jerry Ratcliffe reminisced about the day in 2003 that saw Kournikova come to Charlottesville, Virginia, he remarked:

“We were there to see Anna’s curves, not her serves.”

Sometimes, all you’re looking for from a newspaper is honesty, a little truth-telling, putting the story in simple terms, cutting to the chase.

And you know where you stand when a newspaper lets that sentence through the edit.

Given it was on his beat, Ratcliffe had been at courtside for the $25k Boyd Tinsley Clay Court Classic, a tournament so minor that the presence of Kournikova, trying to find some form, was wildly incongruous.

She was ranked 72nd in the world, and just days earlier had pulled out of a semi-final at a similarly low-profile tournament in Sea Island, Georgia, due to injury. Kournikova’s opponent that day would have been the 16-year-old little-known Maria Sharapova.

By the time Kournikova’s career reached Charlottesville, she was already bordering on desperation, physical pulls, niggles and herniated discs having taken a heavy toll, her confidence inevitably ebbing away. Once a top-10 player, she was in danger of tumbling outside the top 100. A turning point was what she sought, that elusive first singles title.

And so on May 14, 2003 – 17 years ago – Kournikova played what she hoped would be her first of five matches that week.

It turned out to be the very last match she would play on tour, the Russian beaten in three sets by Brazilian Bruna Colosio, a player who sat 384th in the world rankings.

The girl who had bowled over coaching titan Nick Bollettieri with her enthusiasm when springing into his academy barely a decade earlier was finished. She went down not firing but, according to reports from that day, buried by an avalanche of double faults.

Weeks later, in early June, Kournikova was seen in tears in England, pulling out of the grass-court season without playing a match.

The show was over, the series cancelled. Kournikova had just turned 22.

Legendary doubles under the lights:

Capriati / Kournikova

Navratilova / Sánchez Vicario

: 2000 #USOpen pic.twitter.com/FUlOj716su

— US Open Tennis (@usopen) November 1, 2018

Kournikova : “The fame was created by you guys”

Here’s a noteworthy Kournikova quote, snipped from a 2010 Wimbledon news conference I attended.

It came after a hit-and-giggle exhibition doubles match she played alongside Martina Hingis, at a time when both Kournikova and Hingis, once the self-styled ‘Spice Girls’ of tennis, were enjoying retirement.

“You know, the fame and everything, I guess most of it was created by you guys, by the media a lot of times, most of the time the yellow press,” Kournikova said that evening. “[I] never tried to pay attention. I mean, obviously it was a little hard times dealing with it being 16, 17 years old, reading some kind of c**p about yourself, you know. Most of it was made up.”

The trials and tribulations of Anna Kournikova. The sob story writes itself and has been written again and again. Look, she still blames the media. What about those results, Anna? What about your c**ppy results? Nobody made those up.

Of course you could pick apart Kournikova’s career and float the idea it was a washout because she could not fulfil the potential apparent when she reached the 1997 Wimbledon semi-finals, losing to eventual champion and fellow 16-year-old Hingis.

But it would seem beyond churlish, a witless, hardly original reckoning.

Kournikova, the biggest earner in tennis who made millions in endorsements but couldn’t for love nor money lay her hands on a singles crown. Kournikova, the pin-up whose tennis was ancillary to her money-spinning modelling career. Kournikova, the easiest target since the last target was taken down.

It’s all been said, and said too often by those who “were there to see Anna’s curves, not her serves”. By those who knew where she stood in FHM’s top 100 sexiest women, if not the world rankings.

“Tell us about your divorce”

Taken in isolation, any archive transcript of an interview or news conference will speak of a time and a place.

But when the transcripts stack up, that’s when patterns you might have missed at the time begin to emerge.

That’s when you notice what a difference six and a half years can make.

Of the 61 news conferences transcribed and made available by sports event stenographers ASAP Sports, from the start of Kournikova’s career to its 2003 denouement, it is the questions that bookend those that illustrate what a whirring, bewildering rush those years must have been.

In the first of those news conferences, at the 1996 US Open, the first question for Kournikova was a gentle “Why did you win today?”, and the focus remained on her tennis.

By the time those transcripts stopped coming, the last being one from the NASDAQ-100 Open in March 2003, Kournikova departed after being asked, “The story about the divorce, was that any kind of distraction for you at all, preparing for this tournament?”

She and ice hockey player Sergei Fedorov had indeed split, but Kournikova was exasperated by this point.

It is easy for a non-journalist to conflate the news and sport media, and reporters from the front and back of newspapers can be disdainful of each other’s lines of questioning. Kournikova became distrustful, and as her losses had piled up and the criticism followed suit, so she became increasingly resentful.

After tennis, the quiet life

She was asked in that same NASDAQ-100 news conference about her continuing losses, about the criticism she faced, and whether it hurt.

“I can’t change what other people think and all I can do is go and play,” she said. “That’s what I should really be focusing on, is just doing my thing, practising and playing and then if I do well, there will be less criticism. There will be criticism of something else. But at the end of the day, I can’t really do anything with it. There’s going to be one thing or another, so it’s your job, guys, right?”

Whatever she did, Kournikova believed there would be criticism.

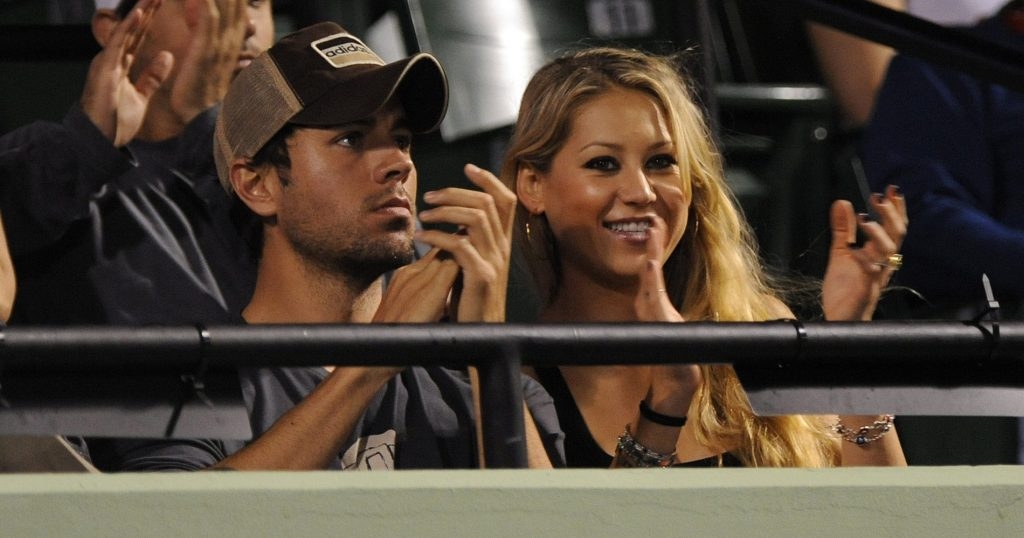

Which perhaps explains to a large part her current life, retired and living privately in Miami, with long-time partner Enrique Iglesias, the Spanish pop singer.

Such is the couple’s secrecy, it is not known whether they are married. They have three children together, including twins that were born in December 2017, without the world having had a clue Kournikova was pregnant.

Tabloid whispers that Kournikova might have been expecting again only emerged days before she gave birth to their third child in January of this year. She keeps that low a profile, and why not?

She and Iglesias remain gossip-mag favourites but rarely give interviews.

She chooses when to accept modelling gigs, skipping strictly to her own beat.

Kournikova : “I was being pulled in every direction”

Kournikova got plenty off her chest in that 2010 Wimbledon news conference, barely letting Hingis interject.

She spoke of how mother Alla tried to protect her during her mid-teens but ran into opposition, discovering “people didn’t really like her that much for that”. Kournikova promised she would “try to guard them as much as I can” if she had a 16-year-old of her own.

“It’s hard,” Kournikova said. “I was being pulled in every single direction. Really there was no guides or rules. My mum and me, we were just learning everything as we were going through it. I was here 15 years old, Wimbledon. I played a Centre Court match. I wasn’t even seeded or anything. It’s a lot for a kid.”

A kid. A kid who’d routinely face questioning from men – usually the reporters were men – on topics they’d balk at broaching with their own teenage daughters.

A kid who reached that fricking Wimbledon semi-final at 16, got to number eight in the world, beat Hingis, Graf, Davenport and Capriati, won two grand slam doubles title and banked over $3.5million from playing – and way more from sponsorship deals that were accelerated by her looks but hinged absolutely on her being an elite sports star in the first place.

A kid who couldn’t help but weep when she knew the tennis dreams of her childhood were over.

A kid whose name became synonymous with failure, when it was a broken body rather than broken resolve that ended her career and our broken moral compass that directed the vultures to their prey.